Frei Otto’s Contribution to the Development of Modern Architecture

Through his contribution as an architect, philosopher, inventor and sculptor, Frei Otto has had a profound impact on the development of modern architecture as we know it today. Although his focus wasn’t on building as much as possible, it is the development of his work that displays his structural and philosophical evolution. He is most well-known for his ‘principle of lightweight construction’ where-in which Otto combines attributes of lightness, openness and mobility to create an efficient nature-inspired architecture. “My hope is that light, flexible architecture might bring about a new and open society.” (Die Zeit, 2003).

Born in Germany in 1925, Otto grew up during the height of the Nationalist Socialist movement. He learnt stone masonry from his father and grandfather, who were both sculptors, while simultaneously holding a strong interest in aviation. When Otto was still a teenager, he was drafted into the German air force as a pilot during WW2, experiencing first-hand the structural possibilities of the thin membranes used in aerospace engineering. The war had a profound influence on the philosophy of his work; in the 2016 documentary ‘Frei Otto: Spanning the Future’, he stated: “The strongest first semester for a student of city planning and architecture is to see a burning city.” Interestingly, it was in a French prisoner of war camp, nearing the end of the war, where Otto first put his ideas to practical use. He was put to work in reconstruction using minimal materials and intuitively begun designing and creating tent-like shelters, strengthening a key element of his design philosophy, ‘how to build more with less.’

For his postgraduate studies he focused predominantly on tent and cable net constructions, completing his doctoral thesis on suspended roofs in 1954 (Meissner, 2015). Consequentially, he begun working with tent-maker, Peter Stromeyer who assisted him in realising a number of his designs during the 1950’s, including the Music Pavilion in 1955, shown in Figure 1. Ottos form finding method was very unique producing extremely precise models in comparison with other contemporaries of his time. Its physical form can be described as the reduction to an optimised expression of structural efficiency, explored later on at his Institute for Lightweight Structures in Stuttgart in what they called “optimized path systems.”

Figure 1: Music pavilion, 1955 (Dezeen)

Figure 2: Seidenhaut, soap film model study (SL Rasch)

Otto, who identifies himself as a “form seeker, and sometimes also a form finder” (Meissner, 2015) developed a concept of form finding that mitigates any distortion, to uncover truly efficient form (Hildebrand, 2015). Otto’s approach to modelling has been likened to that of Gaudí as both architects solicit the aid of gravity through their hanging models. It can be argued that this equilibrated approach to design is problematic due to the logical optimisation hindering artistic expression (Burry, 2016). Otto never saw it like this, however, since his architecture aims to give form the pure artistic beauty of nature, and so, similar to Gaudí, using this modelling approach didn’t stifle his artistic expression, but instead enabled its manifestation.

Although the dematerialisation of architecture has been a popular notion since the industrialisation movement, Otto was unique in his development of a comprehensive society-related idea of architecture while maintaining a ‘lightness against brutality’ (Nerdinger, 2005) in direct contrast with the heavy, dogmatic structures of Nazi and Soviet architecture which had plagued the former half of the twentieth century. Alluding to his focus on design philosophy over physical structure, Otto has stated “I built little. But I devised many “castles in the air.”” (Meissner, 2015).

As a response to the destruction from the war, many architects were turning their attention to the planning of the city. Following the dissolution of CIAM (International Congresses of Modern Architecture) due to public scrutiny, 1958 saw the formation of GEAM (Mobile Architecture Study Group), of which Otto was a member. The group’s main aim was to scrutinise and criticise the contemporary conditions of architecture and planning, promoting the concept of mobile architecture as a solution for the rigid, formal planning that dominated European cities. (Escher, 2016).

In contrast with CIAM, GEAM was more technically orientated; members shared interests in biological systems and cybernetic techniques and incorporated these into their designs. Furthermore, each member had first-hand experience of living in a society controlled by totalitarian regimes and so, ‘individual mobility’ was of utmost importance, hence the incorporation of ‘mobile architecture’ in the group name. Architecture, in these architects’ minds, should be adaptive and should change in accordance with the needs of the individual rather than enforcing constraints on masses in society; this in keeping with the psychological freedom and individual agency required for a healthy society. Otto’s philosophy closely aligned with this since he was fascinated by the connection architecture had with other areas of life. It is unsurprising then that GEAM was strongly opposed to the mass roll out of low-quality building stock and standardised city layouts done to replace the large areas of cities destroyed during the war (Escher, 2016).

Although designs produced by the group were ‘utopian’ in nature, they did have strong connections to real world issues. For example, at the same time as Ehrenkrantz’s SCSD system in America, the GEAM group were also experimenting with personalised ‘adaptive’ architecture (Escher, 2016). Three members of the group, including Otto, were involved in designing different systems for adaptable units of space (Jan Trapman, 1957).

Figure 3: Jan Trapman, Kristallbouw, c. 1957 (Moravanszky, 2017)

Otto was aware of the movement towards “mass production” the construction industry was exhibiting and realised that society was not quite ready for his elegant, mobile design ideas that promoted dematerialisation. Since he did not want to build permanent, heavy structures that many requested he instead decided to initiate a private research institute in Berlin, the Institute for Development of Lightweight Constructions, in 1958 (Glaeser, 1972). This change of direction into a focus on research was perhaps the best decision for the development of his practise as he could discuss and teach his ideas to the younger generation, directly changing the narrative of modern architecture. Following this he was recommended to head the new Institute for Lightweight Structures in Stuttgart, a defining moment in Otto’s career.

A large amount of ground-breaking research on cable net structures was carried out here, much of which helped realise Otto’s award-winning German Pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal, as shown in Figure 4, employing his signature anti-classic curves in additive arrangements. This large-scale, tensile structure was one of Otto’s few opportunities to demonstrate their benefits from his ideas and research that had previously been contained to concepts and models. It is far more economic to bridge large-scale spans in tension as the length to volume ratio is far greater than in other structures, thereby increasing the structures tensile strength.

Figure 4: Expo ’67 German Pavilion, Montreal 1967 (metalocus)

In 1960, just after finishing his studies on water tensioned membranes, Otto met Gerhard Helmke, a professor of biology and anthropology at the Technical University of Berlin. The following year they founded an interdisciplinary research group, ‘Biology and Building’ together also at the Technical University of Berlin (Nerdinger, 2005). This created a space for collaboration and experimentation, as depicted in Figure 5, between biologists, palaeontologists and architects. Theories, ideas and information could then be shared as a method to bridge the gap between architecture and nature (Meissner, 2015).

Figure 5: Otto working on a pneumatic experiment, 1973 (Fabricius, 2016)

Through this marrying of minds, a plethora of research was undertaken attempting to bridge the gap between Otto and Helmcke’s respective areas of expertise. Together they developed theories of biotechnics to assign structural properties to a cosmology of objects made up of both living and non-living nature; later on, the BIC method materialised from this (Fabricius, 2016). Furthermore, both scholars suspected that what they called the ‘pneu’ was the fundamental stage of biological form from which all other form has evolved. If this was the case, it would serve as an indispensable interdisciplinary bridge for their search for a greater method of structural optimisation.

Otto later stated that this research became more important to him than architectural construction (Meissner, 2015). They analysed hundreds of facets of nature, different spider webs, tree structures, among other things, dedicating innumerable hours gathering evidence in favour of ‘pneu’ as the fundamental structure. Otto’s pneu theory, however, seemed to indicate a ‘systems paranoia’ also indicates a kind of ‘systems paranoia’ in which the collected data appears to have a universal, ubiquitous quality due to the lack of boundary conditions set by the system (Fabricius, 2016). Essentially the definition for vague was too ‘vague’ and ‘all-encompassing.’ Although Otto never answered their question, this research inspired a movement of natural design, especially in the universities in which Otto taught and contributed greatly to the field of pneumatic structures.

Figure 6: A diagram sketch depicting connections within the “pneu” (Fabricius, 2016)

Since pneumatically distended membranes only require air pressure to support them, they are essentially in a constant state of weightlessness. Due to his extensive research on the topic, Otto formulated the first coherent theory of this building type. He experimented with potential forms and after applying his knowledge of tent structures, he was able to reduce and vary the membrane height and provide interior drainage in analogy to the high-and-low-point principle (Glaeser, 1972).

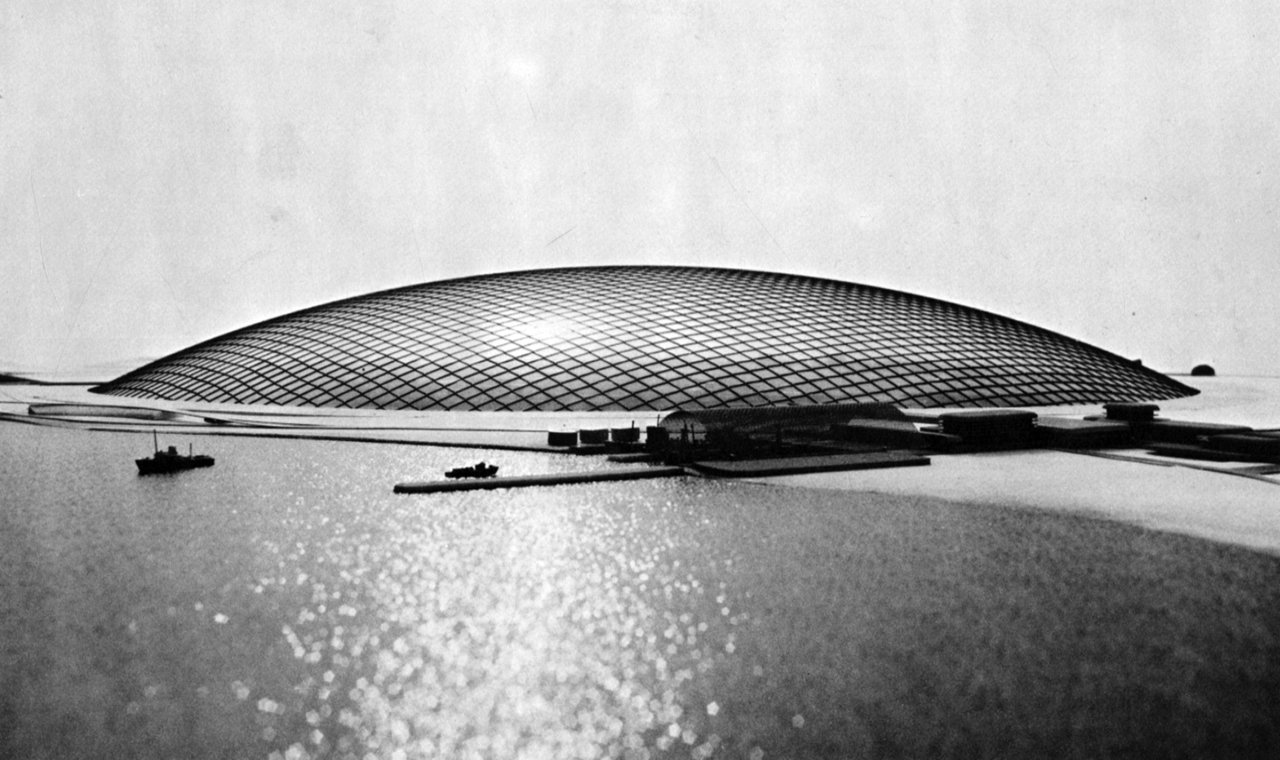

In 1971, in a project with Ewald Bubner and Kenzo Tange, Otto designed an Arctic City Envelope, shown in Figure 7. The thin membrane dome shaped envelope, inspired by pneumatic design, functions as an enclosure enabling a conditioned environment within. The structure consists of a steel cable net superstructure supporting double layered transparent foil. Pneumatic architecture has successfully been incorporated into architectural design in recent years, a good example being by the explorative architect, Michael Pawlyn, a prominent figure in regenerative design and biomimicry. He was involved in the design of the Eden Project, shown in Figure 8, a visitor attraction greenhouse centre, the form of which was inspired by bubbles. This bears some similarity to Otto’s Arctic City Envelope; both structures consist of a steel superstructure however Pawlyn’s is extremely lightweight and incorporates Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome design to support itself structurally.

Figure 7: The Arctic City Project, 1971 (Hidden Architecture)

Figure 8: The Eden Project, 2000 (Eden Project)

Otto has taken on many roles throughout his career, never truly adhering to the boundaries of the traditional definition of architect. Similar in this way to Eladio Dieste, he has been likened to an inventor since for many of his designs he fashioned bespoke details and equipment, including cable clamps and alternate measuring tools, to aid in the function of these structures. These additional ‘non-structures’ were largely used in his large-scale retractable roofs, although not many of these were constructed. Otto designed some of these to retract automatically, giving the structure even greater mobility and deployability. For Otto, the qualities of mobility, deployability and lightness represented a truly adaptive architecture minimising waste and reducing unnecessary future production.

Figure 9: The Aviary at Hellerbrunn Zoo, 1980 (Dezeen)

“We have not yet experienced the fragile, perhaps even ephemeral, architecture of the physical and psychical integration of man into his environment. But we seek the architecture of understanding and of the great vision of a synthesis of all the objects of nature.” (Meissner, 2015)

Although Otto gave up practising architecture in 1970 to become a full-time consultant, he did complete one final piece in 1980, the Aviary at Hellerbrunn Zoo, shown in Figure 9. This form of ethically driven minimalism is arguably Otto’s greatest architectural achievement. He manages to synthesise nature and structural efficiency in a light, translucent canopy that allows you to forget that you are standing beneath an enclosure and feel at one with the surrounding nature. This also creates a much more comfortable and ethical way of keeping the animals. The site spans 5000 square metres and reaches 18m in height. Structurally, staffs have been used to hold the compressive forces, while a thin steel mesh envelope acts in tension.

Even though Otto’s architecture is neither loud nor assertive in nature, he has nonetheless managed to garner great traction and intrigue from both public and professional bodies. As one of the pioneers of early, pre-digital parametric design, his chosen method of finding form straddles the boundary of the architectural and engineering practice, strengthening the relationship between the two disciplines. Some deem his ideology naïve, others as “endearingly silly” and as a product of its time (Murphy, 2015), however, this seems to be a shallow misinterpretation of the depth of Otto’s research and the relation of this research to his projects. Throughout his career he has shone a light on a plethora of areas deeply connected to structure and form that had previously been, and still often continue to be, disregarded, including those relating to biology, anthropology and psychology. These aspects of design are becoming increasingly important for our current climate in which mental, physical and environmental wellbeing are becoming more unstable. And so, for obvious reason, Otto’s social and architectural critiques and musings have caused a ripple effect in later generations, changing the perception of modern architecture and the potential of contemporary practice. In this way, Otto’s optimistic, alternative narrative serves as a reminder that there is another, more sympathetic way to approach design and construction that connects us deeper with the world in which we exist.

Bibliography

Aldinger, Irmgard Lochner. “Frei Otto: Heritage and Prospect.” International Journal of Space Structures 31, no. 1 (2016): 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266351116649079.

Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu. “Image Spaces: Biology and Building.” Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Accessed March 27, 2022. https://www.smb.museum/en/exhibitions/detail/image-spaces-biology-and-building/.

Burkhardt, Berthold. “Natural Structures - the Research of Frei Otto in Natural Sciences.” International Journal of Space Structures 31, no. 1 (2016): 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266351116642060.

Burry, Mark. “Antoni Gaudí and Frei Otto: Essential Precursors to the Parametricism Manifesto.” Architectural Design 86, no. 2 (2016): 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2021.

Escher, Cornelia. “Nested Utopias: GEAM’s Large-Scale Designs.” Re-Scaling the Environment, 2016, 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783035608236-006.

Fabricius, Daniela. “Architecture before Architecture: Frei Otto's ‘Deep History.’” The Journal of Architecture 21, no. 8 (2016): 1253–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1254667.

Glaeser, Ludwig. The Work of Frei Otto. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1972.

Goldsmith, Nicholas. “The Physical Modeling Legacy of Frei Otto.” International Journal of Space Structures 31, no. 1 (2016): 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266351116642071.

Meissner, Irene, Möller Eberhard, and Frei Otto. Frei Otto Forschen, Bauen, Inspirieren = Frei Otto: A Life of Research, Construction and Inspiration. München: Edition Detail, 2017.

Murphy, Douglas. “Frei Otto (1925-2015).” Architectural Review, July 21, 2020. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/frei-otto-1925-2015.

Oliva Salinas, Juan G., Marisela Mendoza, and Edwin González Meza. “Reflections on Frei Otto as Mentor and Promoter of Sustainable Architecture and His Collaboration with Kenzo Tange and Ove Arup in 1969.” Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures 59, no. 1 (2018): 87–100. https://doi.org/10.20898/j.iass.2018.195.900.

Otto, Frei, and Berthold Burkhardt. Occupying and Connecting: Thoughts on Territories and Spheres of Influence with Particular Reference to Human Settlement. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, 2011.

Otto, Frei, and Bodo Rasch. Frei Otto, Bodo Rasch: Finding Form: Towards an Architecture of the Minimal: The Werkbund Shows Frei Otto, Frei Otto Shows Bodo Rasch: Exhibition in the Villa Stuck, Munich, on the Occasion of the Award of the 1992 Deutscher Werkbund Bayern Prize to Frei Otto Und Bodo Rasch. Stuttgart: Edition Menges, 1995.

Otto, Frei, and Winfried Nerdinger. Frei Otto: Complete Works: Lightweight Construction, Natural Design. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2005.

Spuybroek, Lars. “The Structure of Vagueness.” Peformative Architecture, 2005, 167–82. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203017821-13.

Trapman, Jan. “Kristalbouw. Een bijdrage tot de woningbouw,” Bouw 12, no. 11 (1957) 230–40